Volume 5, Issue 3 (10-2021)

EBHPME 2021, 5(3): 166-175 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Khodayari-Zarnaq R, Torkzadeh L, Heydari S, Rahmani H, Mir N, Jalilian H. The Survey of Family /Community involvement in Schools’ Health Planning and Policymaking. EBHPME 2021; 5 (3) :166-175

URL: http://jebhpme.ssu.ac.ir/article-1-334-en.html

URL: http://jebhpme.ssu.ac.ir/article-1-334-en.html

Rahim Khodayari-Zarnaq

, Leila Torkzadeh

, Leila Torkzadeh

, Somayeh Heydari

, Somayeh Heydari

, Hojjat Rahmani

, Hojjat Rahmani

, Nazanin Mir

, Nazanin Mir

, Habib Jalilian *

, Habib Jalilian *

, Leila Torkzadeh

, Leila Torkzadeh

, Somayeh Heydari

, Somayeh Heydari

, Hojjat Rahmani

, Hojjat Rahmani

, Nazanin Mir

, Nazanin Mir

, Habib Jalilian *

, Habib Jalilian *

Department of Health Services Management, School of Public Health, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran , jalilian.mg86@gmail.com

Full-Text [PDF 1278 kb]

(982 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2896 Views)

Full-Text: (483 Views)

Background: Schools play a crucial role in developing a healthy lifestyle and community participation, especially family participation, which is essential to schools’ success in achieving this role. This study aimed to examine the family/community involvement in schools’ health planning and policymaking from the principal and lead health education teacher in Tabriz, Iran.

Methods: This cross-sectional study was conducted in 2016. The statistical population included all school principals and lead health education teachers in Tabriz, Iran. A total of 93 schools were included. A systematic random sampling method was used for data collection. Data were collected using the School Health Profiles. The content validity of the profile was revised by an expert involved in school health. The questionnaire’s reliability was calculated by internal consistency and Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Data were analyzed using SPSS22. Mann-Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests were applied to examine the difference between the type of school (in terms of ownership, gender, and grade) and the school’s percentage that attracts family/community participation.

Results: According to the results, only 53.80 % of schools actively collaborated with students’ families in developing and implementing policies and programs related to health school. The majority of schools (83.30 %) provided parents with educational content on nutrition and healthy eating, while only 40 % of them provided parents with educational content on HIV prevention, STD prevention, teen pregnancy prevention, and asthma. Moreover, more than 50 % of schools worked with other staff groups about health education activities. In most schools (73.30 %), health education teachers worked with physical education staff, while in 53.30 % of them, health education teachers worked with nutrition or service staff on health education activities.

Conclusion: Given a low percentage of school and family/community partnerships in school health-promotion programs in most dimensions, comprehensive and integrative planning must be implemented to create engagement and collaboration with other community sectors.

Key words: Family involvement, Community involvement, School health policy, School health planning

Schools play an essential role in promoting and modifying students’ lifestyles and have an important role in promoting community health through interventions like parental training, nutrition programs, physical education, and supportive services (1-3). On the other hand, one of the beneficial strategies for motivating students towards health-promoting behaviors is parental involvement in school health policies and programs (4). Parental involvement in schools means parental engagement with the school staff for health promotion, learning about children and adolescents (5). Parents and family members can play a significant role in nurturing their children’s education and health and guiding them through different school activities. It has been shown that students represent better behavior and social skills, fewer health risk behaviors, and higher academic achievement when parents are engaged in schools. Besides, school efforts for improving student health are more successful when parents are more involved (6).

The participation of all actors, pillars, and elements related to education from teachers to students, family, and health professionals have been confirmed for achieving better and sustained health of the students (7). School-family partnership and collaboration result in reinforcing students’ learning and health-promotion in various settings such as home, school, and community (6). The CDC and SHAPE (the Society of Health and Physical Educators) America (2013) has introduced some measures, including physical education, physical activity during school (e.g., physical activity breaks), physical activity before and after school (e.g., walk to-school programs), participation, and role modelling, family engagement, and community involvement etc. that can assist schools in implementing a multi-component Comprehensive School Physical Activity Program (CSPAP) (8).

Community agencies can help schools improve student health and education outcomes (9). Besides, many schools and communities together are implementing “community schools“ that amalgamate resources from various community agencies for providing an “integrated focus on academics, health and social services, youth and community development, as well as community engagement” (9).

By working together with students, families, and community service providers, the school nurse (10, 11) and the school physician (12) can not only play crucial roles in preventing, detecting, and treating health problems but also can improve the educational performance of all students (9).

Parental involvement is a principle strategy in primary education among children and has a detrimental effect on healthy growth and health-related behavior (4). According to a study conducted in the United States, there is a direct association between family involvement and school nutrition and physical activity policies (13). Despite the importance of family and community involvement in school planning and policymaking, one major problem in most schools is the low level of community participation in school affairs (14).

Given the importance of family/community participation in planning and school policymaking in the field of health, and considering that no study has been conducted regarding the family/community participation in the planning process and school policy in the field of health, this study aimed to examine the family/ community participation in the planning process and schools’ policymaking concerning health in Tabriz.

Materials and Methods

This study is a cross-sectional one. The statistical population included all principals and lead health education teachers of all schools in Tabriz, Iran, in 2016. Sampling conducted using stratified systematic random sampling. Each of the five municipal zones of Tabriz city was placed in one stratify. Out of 800 schools in five districts, 93 schools were selected using a systematic random sampling method according to the number of schools in each zone and tailored to ownership, gender, and educational grade.

Data collection tools

Data were collected using the School Health Profiles (15). The School Health Profiles is a survey system assessing school health policies and practices in states, large urban school districts, and territories. The Profiles survey was developed in 1996 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in collaboration with state and local health agencies to monitor middle and high school health standards. This survey is conducted biennially by education and health agencies among middle and high school principals and lead health education teachers (16).

This profile includes different health topics. However, in the present study, only family and community involvement were explored. The questionnaire was completed individually by the schools’ principals and health education teachers in the researcher’s presence.

The part of the profile related to the principal school consists of six questions:

After translating the English version of the profile to Persian by the researcher team, the profile’s content validity was revised by an expert involved in school health. The questionnaire’s reliability was calculated by internal consistency, and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for principal and lead health education teachers was 0.81.7 and 0.94.7, respectively.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS22. Descriptive statistics (frequency and percent) were used to assess the level of family/community participation in school health programs and policies. Mann-Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests were applied to examine the difference between the type of school (in terms of ownership, gender, and grade) and the school’s percentage that attracts family/community participation.

The Ethics Committee approved this study of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (Reference NO: IR.TBZMED.REC.2017.162). The required permissions for distributing the questionnaire were obtained from the Department of Education, and the necessary coordination was conducted with the provincial health system.

Results

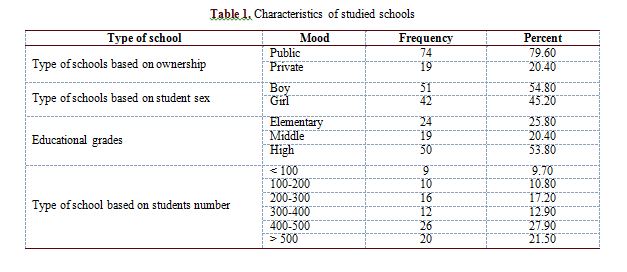

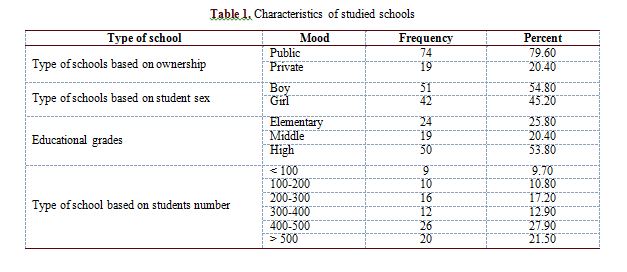

A total of 93 schools were included in this study. School characteristics are shown in Table 1.

As shown in Table 2, 5 % of schools had given homework or activities related to health education to students at home with their parental collaboration. The majority of schools (71 %) informed parents regarding school health services and programs via different communication methods. In comparison, only 35.50 % of schools provided parents and families with necessary information on communicating with their child about sexual issues. The association between the type of schools’ ownership, providing necessary information, educating parents regarding how to communicate with their child about sex (P-value < 0.0001), and monitor their child (P-value < 0.0001) was significant. A significant association was found between students’ educational level and family involvement as health volunteers in delivering health education activities and services. 26 % of elementary schools, 20 % of middle schools, and 54 % of high schools have succeeded in attracting parental involvement as school volunteers.

According to Table 3, most schools (83.30 %) provided parents with educational content on nutrition and healthy eating. Only 40 % of them provided parents with educational content on HIV prevention, STD prevention, or teen pregnancy prevention, as well as asthma. Moreover, school students’ gender was significantly associated with educational topics, namely HIV prevention, STD prevention, or teen pregnancy prevention, as well as preventing student bullying and sexual harassment, including electronic aggression (i.e., cyber-bullying) (P-value < 0.05).

In the majority of schools (73.30 %), health education teachers worked with physical education staff. In comparison, in 53.30 % of schools, health education teachers worked with nutrition or service staff on health education activities (Table 4).

Discussion

The findings showed that a lower percentage of schools could attract family/community involvement in schools’ health activities and policies. Approximately two-thirds of schools had no activity on topics such as providing necessary information and education to parents about how to communicate with their child about sexual issues and monitor their child’s sexual behaviors. More than 50 % of schools did not involve families in consultation and education and did not provide them with necessary information about sexual health services. Because of the social and cultural barriers in Muslim countries like Iran, sexual topics are seen as taboo, and many believe that the education of such topics can lead to deviation of sexual behavior in students. Given that cultural and biological factors highly influence human sexual behaviors, sexual education by schools, media, or parents is not easily done (17). It has been shown that high school students are more likely to obtain sexual-information from movies, magazines, media, and close friends (18). By decreasing sexual intercourse age, premature puberty, and increasing marriage age in Iran (19), lack of knowledge and adolescents’ education on sexual issues can lead to the appearance of high-risk sexual behaviors.

According to the School Health Profile report in 2016 that is undertaken every two years in the United States, only 29 % of schools in big cities had given education and necessary information to parents on how to communicate with children on sexual issues, which this figure was at a lower level in comparison with our results. But, 62 % of schools in the big cities in the United States had given the necessary information to parents for their child’s sexual issues monitoring, which in the current study, this figure was estimated at 36 %.

A study by Weaver et al. (20) demonstrated that although parents indicated that they wish to be involved in their child’s sexual health education, most of them had not discussed any sexual health education with their child. Parents also showed that they want more information from schools regarding sexual health education topics, sexuality in general, and communication strategies to assist them in providing education at home.

Using social organizations is one way to teach social skills and sex education for children and adolescents. Although these organizations can play a more active role in developing a trust-based relationship between parents and schools, the present study findings showed no collaboration between social organizations associated with health and family in more than half of schools. Hence, it seems necessary to adopt appropriate policies and programs to use these organizations’ potential in schools. In the United States, the partnership between families and social organizations has been estimated at 77.50 % (21), higher than our results.

Although increased family/community involvement in schools has been emphasized in the Fundamental Transformation Document of Education in the sixth national development plan of Iran (22), in this study, students’ families had active participation in developing and implementing policies and programs related to school health only in half of the schools. The parental involvement rate in developing and implementing policies and programs was at a moderate level, which affects the success rate of schools’ programs and policies, as active family engagement in schools’ planning and policymaking causes a sense of ownership and increased families commitment in the proper implementation of schools programs. The study of Kim et al. (13) has shown that family engagement can positively influence school nutrition and physical activity policies and practices.

The low family engagement in school health topics can arise from different reasons, such as many work and family businesses and time shortage. However, schools have not correctly understood the importance of family engagement in maintaining and promoting student health profile and have not carried out enough effort to attract their participation. The level of family involvement can be improved through attending children’s parents as representatives on schools’ boards or parent-teacher meetings. However, an essential issue in the development and implementation of family engagement strategies is to consider the socio-economic and cultural conditions of families, providing the possibility of family engagement. The study of Yolcu et al. (23) indicated that the effect of parents’ participation in school decision making varied in the socio-economic levels of the areas where schools were located, and also the difficulties experienced by the school administrators and parents in the process of their participation in schools varied with the socio-economic levels of schools.

Moreover, in designing health information content to increase families’ knowledge, most schools focused on healthy nutrition education, tobacco use prevention, physical activity, and diabetes, respectively. However, in designing educational content for parents, less than half of schools had addressed topics such as AIDS prevention, STD prevention, teen pregnancy, violence prevention, and cyber sexual harassment. In 2018, the prevalence of AIDS among people aged 15-49 years old in Iran was 0.1 %, and the number of people living with AIDS was 66,000, according to the statistics (9). AIDS prevention training is one of the topics that has been addressed in the field of socialization of health. Recently, easy access to electronic communication devices and the widespread attendance of children and adolescents in cyberspace have exposed them to a new type of violence called electronic aggression. Therefore, the prevalence of internet-harassment in adolescents has been reported as 1–61 % (24). This electronic aggression can have dangerous consequences on students and parents, leading to social isolation and suicide in adolescents later. Therefore, in educational content offered to families, some important issues such as social networks-related topics, communication applications, and monitoring of these networks’ use by children how to behave with cyber abuses should be included.

Given that necessary education for parents about tobacco use prevention is being performed in half of the schools. However, the prevalence of smoking, alcohol, chewing tobacco in Iranian adolescents aged 14-19 years old have been estimated at 17 %, 15 %, and 10 %, respectively (25). Since smoking usually occurs in early adolescence and continues until adulthood, proper and timely education for parents and adolescents can help prevent smoking’s adverse effects.

The finding of this study showed that only half of the schools had given homework or activities related to health education to students for being done at home with the participation of their parents, while in urban schools of the United States, this figure estimated at 62 % (26). Since doing homework at home is a tool for stabilizing learning in students, the quantity and quality of homework and parental participation in doing these should be in such a way that they boost the relationship between students and parents and improve students’ performance, and at the same time making a positive relationship between parents and teachers. The study of Núñez et al. (27) showed a reciprocal association between students’ achievement and parental involvement. They indicated that children’s achievements affect the rate and type of parental participation, and conversely, the student’s perception of their parent’s involvement in homework affects their achievements (27).

In the current study, lead health education staff worked with physical activity staff and the school health council in most schools. However, in some studies in Iran, the prevalence of depression among children and adolescents reported 43.55 % (28), and the majority of overweight and obese Iranian children aged less than five years were reported 9 % and 10 %, respectively (29). In comparison, overweight and obesity in children aged 7–18 were 9 % and 3 %, respectively (30). In this study, the participation rate of the staff of nutrition, social services, and mental health was lower compared to other related groups, which represents the failure to understand the importance of mental health topics for policymakers and authorities of health-promotion programs in schools.

Since the questionnaire was completed by the school principals and lead health education teachers, a self-report method was used to determine the level of family/community involvement in school health policies and programs, affecting the accurate estimation of participation level.

Conclusion

Given a low percentage of school and family/community partnerships in school

health-promotion programs in most dimensions, comprehensive and integrative planning is required to create engagement and collaboration with other community sectors.

Implications

The results of this study are indicative of the main frail of schools in attracting parental participation and their training regarding how to communicate with their child in the field of sexual topics and how to manage and monitor their children’s sexual behaviors, which increase the incidence of high-risk sexual behaviors among adolescents. Given that different social groups in terms of sexual literacy are at different levels, policymakers should perform educational policies based on educational groups’ needs and various areas. In other words, cultural and religious barriers in Iran have confronted transmission and education of sexual topics with the challenge. Besides, in many cases, sexual education topics will face the religious authorities’ opposition. Hence, the use of mass media to educate such topics considering Iran’s religious history required authorities’ support and commitment. Therefore, policies expanding in this domain should be formulated and implemented with the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Education, the Radio and Television Organization, non-governmental organizations, and the support of authorities. The present study also indicated that schools with groups such as nutrition or eating service staff, mental health or social services staff were at a lower level compared with other groups. So,

given the fundamental role of the two mentioned groups in students’ health promotion, enough concentration on attracting these groups’ participation by schools is necessary.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for supporting this research. We also wish to express thanks to individuals who participated in this study.

Conflict of interests

The authors declared no conflict of interests.

Authors’ contributions

Jalilian H and Khodayari-Zarnaq R designed research; Jalilian H, Heydari S, Torkzadeh L, Mir N and Rahmani H conducted research; Jalilian H and Heydari S analyzed data; and Jalilian H and Heydari S wrote manuscript. Jalilian H had primary responsibility for final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Tabriz

University of Medical Sciences (Grant Number: IR.TBZMED.REC. 64.61).

Methods: This cross-sectional study was conducted in 2016. The statistical population included all school principals and lead health education teachers in Tabriz, Iran. A total of 93 schools were included. A systematic random sampling method was used for data collection. Data were collected using the School Health Profiles. The content validity of the profile was revised by an expert involved in school health. The questionnaire’s reliability was calculated by internal consistency and Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Data were analyzed using SPSS22. Mann-Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests were applied to examine the difference between the type of school (in terms of ownership, gender, and grade) and the school’s percentage that attracts family/community participation.

Results: According to the results, only 53.80 % of schools actively collaborated with students’ families in developing and implementing policies and programs related to health school. The majority of schools (83.30 %) provided parents with educational content on nutrition and healthy eating, while only 40 % of them provided parents with educational content on HIV prevention, STD prevention, teen pregnancy prevention, and asthma. Moreover, more than 50 % of schools worked with other staff groups about health education activities. In most schools (73.30 %), health education teachers worked with physical education staff, while in 53.30 % of them, health education teachers worked with nutrition or service staff on health education activities.

Conclusion: Given a low percentage of school and family/community partnerships in school health-promotion programs in most dimensions, comprehensive and integrative planning must be implemented to create engagement and collaboration with other community sectors.

Key words: Family involvement, Community involvement, School health policy, School health planning

Introduction

The participation of all actors, pillars, and elements related to education from teachers to students, family, and health professionals have been confirmed for achieving better and sustained health of the students (7). School-family partnership and collaboration result in reinforcing students’ learning and health-promotion in various settings such as home, school, and community (6). The CDC and SHAPE (the Society of Health and Physical Educators) America (2013) has introduced some measures, including physical education, physical activity during school (e.g., physical activity breaks), physical activity before and after school (e.g., walk to-school programs), participation, and role modelling, family engagement, and community involvement etc. that can assist schools in implementing a multi-component Comprehensive School Physical Activity Program (CSPAP) (8).

Community agencies can help schools improve student health and education outcomes (9). Besides, many schools and communities together are implementing “community schools“ that amalgamate resources from various community agencies for providing an “integrated focus on academics, health and social services, youth and community development, as well as community engagement” (9).

By working together with students, families, and community service providers, the school nurse (10, 11) and the school physician (12) can not only play crucial roles in preventing, detecting, and treating health problems but also can improve the educational performance of all students (9).

Parental involvement is a principle strategy in primary education among children and has a detrimental effect on healthy growth and health-related behavior (4). According to a study conducted in the United States, there is a direct association between family involvement and school nutrition and physical activity policies (13). Despite the importance of family and community involvement in school planning and policymaking, one major problem in most schools is the low level of community participation in school affairs (14).

Given the importance of family/community participation in planning and school policymaking in the field of health, and considering that no study has been conducted regarding the family/community participation in the planning process and school policy in the field of health, this study aimed to examine the family/ community participation in the planning process and schools’ policymaking concerning health in Tabriz.

Materials and Methods

This study is a cross-sectional one. The statistical population included all principals and lead health education teachers of all schools in Tabriz, Iran, in 2016. Sampling conducted using stratified systematic random sampling. Each of the five municipal zones of Tabriz city was placed in one stratify. Out of 800 schools in five districts, 93 schools were selected using a systematic random sampling method according to the number of schools in each zone and tailored to ownership, gender, and educational grade.

Data collection tools

Data were collected using the School Health Profiles (15). The School Health Profiles is a survey system assessing school health policies and practices in states, large urban school districts, and territories. The Profiles survey was developed in 1996 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in collaboration with state and local health agencies to monitor middle and high school health standards. This survey is conducted biennially by education and health agencies among middle and high school principals and lead health education teachers (16).

This profile includes different health topics. However, in the present study, only family and community involvement were explored. The questionnaire was completed individually by the schools’ principals and health education teachers in the researcher’s presence.

The part of the profile related to the principal school consists of six questions:

- Providing parents and families with necessary information regarding how to communicate with their child about sex;

- Providing parents with necessary information regarding how to monitor their child such as setting parental expectations and keeping track of their child as well as responding when their child breaks the rules;

- Involving parents in the delivery of health education activities and services as school volunteers;

- Linking parents and families to health services and programs in the community;

- Does the school provide electronic (e.g., e-mails, school websites), paper (e.g., flyers, postcards), or oral (e.g., phone calls, parent seminars) communication to inform parents about school health services and programs?

- Have students’ families helped design or implement school health policies and programs during the past two years?

- During this school year, have any health education staff worked with each of the other health-related groups

- During this school year, have your school provided parents and families with health information designed to increase parent and family knowledge of different topics?

- During this school year, have teachers in this school given students homework assignments or health education activities to do at home with their parents’ assistance?

After translating the English version of the profile to Persian by the researcher team, the profile’s content validity was revised by an expert involved in school health. The questionnaire’s reliability was calculated by internal consistency, and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for principal and lead health education teachers was 0.81.7 and 0.94.7, respectively.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS22. Descriptive statistics (frequency and percent) were used to assess the level of family/community participation in school health programs and policies. Mann-Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests were applied to examine the difference between the type of school (in terms of ownership, gender, and grade) and the school’s percentage that attracts family/community participation.

The Ethics Committee approved this study of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (Reference NO: IR.TBZMED.REC.2017.162). The required permissions for distributing the questionnaire were obtained from the Department of Education, and the necessary coordination was conducted with the provincial health system.

Results

A total of 93 schools were included in this study. School characteristics are shown in Table 1.

As shown in Table 2, 5 % of schools had given homework or activities related to health education to students at home with their parental collaboration. The majority of schools (71 %) informed parents regarding school health services and programs via different communication methods. In comparison, only 35.50 % of schools provided parents and families with necessary information on communicating with their child about sexual issues. The association between the type of schools’ ownership, providing necessary information, educating parents regarding how to communicate with their child about sex (P-value < 0.0001), and monitor their child (P-value < 0.0001) was significant. A significant association was found between students’ educational level and family involvement as health volunteers in delivering health education activities and services. 26 % of elementary schools, 20 % of middle schools, and 54 % of high schools have succeeded in attracting parental involvement as school volunteers.

According to Table 3, most schools (83.30 %) provided parents with educational content on nutrition and healthy eating. Only 40 % of them provided parents with educational content on HIV prevention, STD prevention, or teen pregnancy prevention, as well as asthma. Moreover, school students’ gender was significantly associated with educational topics, namely HIV prevention, STD prevention, or teen pregnancy prevention, as well as preventing student bullying and sexual harassment, including electronic aggression (i.e., cyber-bullying) (P-value < 0.05).

In the majority of schools (73.30 %), health education teachers worked with physical education staff. In comparison, in 53.30 % of schools, health education teachers worked with nutrition or service staff on health education activities (Table 4).

Table 2. School and family/community partnership in different scopes

*P < 0.01 was considered as significant

Table 3. The percentage of schools regarding designing and providing various educational contents to increase families’ knowledge

*P < 0.05 was considered as significant

| Activity | Percent | The number of students (P) | Gender (P) | Educational grade (P) | Ownership (P) |

| Providing parents and families with necessary information regarding how to communicate with their child about sex | 35.50 | 0.36 | 0.63 | 0.08 | < 0.0001* |

| Providing parents with necessary information regarding how to monitor their child, such as setting parental expectations and keeping track of their child as well as responding when their child breaks the rules | 36.60 | 0.09 | 0.78 | 0.15 | < 0.0001* |

| Involving parents in the delivery of health education activities and services as school volunteers | 48.40 | 0.65 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 0.92 |

| Linking parents and families to health services and programs in the community | 46.20 | 0.52 | 0.8 | 0.00 | 0.15 |

| Does the school provide electronic (e.g., e-mails, school web site), paper (e.g., flyers, postcards), or oral (e.g., phone calls, parent seminars) communication to inform parents regarding school health services and programs? | 71.00 | 0.02 | 0.19 | 0.78 | 0.78 |

| Students’ families have an active collaboration in developing and implementing policies and programs related to health school | 53.80 | 0.94 | 0.31 | 0.91 | 0.91 |

Table 3. The percentage of schools regarding designing and providing various educational contents to increase families’ knowledge

| Educational topics | Percent | The number of students (P) | Gender (P) | Educational grade (P) | Ownership (P) |

| HIV prevention, STD prevention, or teen pregnancy prevention | 40.00 | 0.28 | 0.03* | 0.16 | 0.80 |

| Tobacco use prevention | 56.70 | 0.50 | 0.17 | 0.30 | 0.71 |

| Physical activity | 56.70 | 0.91 | 0.29 | 0.20 | 0.66 |

| Nutrition and healthy eating | 83.30 | 0.82 | 0.31 | 0.48 | 0.41 |

| Asthma | 40.00 | 0.60 | 0.36 | 0.15 | 0.32 |

| Food allergies | 43.30 | 0.50 | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.39 |

| Diabetes | 56.70 | 0.50 | 0.17 | 0.40 | 0.71 |

| Preventing student bullying and sexual harassment, including electronic aggression (i.e., cyber-bullying) | 40.00 | 0.06 | 0.03* | 0.09 | 0.32 |

Discussion

The findings showed that a lower percentage of schools could attract family/community involvement in schools’ health activities and policies. Approximately two-thirds of schools had no activity on topics such as providing necessary information and education to parents about how to communicate with their child about sexual issues and monitor their child’s sexual behaviors. More than 50 % of schools did not involve families in consultation and education and did not provide them with necessary information about sexual health services. Because of the social and cultural barriers in Muslim countries like Iran, sexual topics are seen as taboo, and many believe that the education of such topics can lead to deviation of sexual behavior in students. Given that cultural and biological factors highly influence human sexual behaviors, sexual education by schools, media, or parents is not easily done (17). It has been shown that high school students are more likely to obtain sexual-information from movies, magazines, media, and close friends (18). By decreasing sexual intercourse age, premature puberty, and increasing marriage age in Iran (19), lack of knowledge and adolescents’ education on sexual issues can lead to the appearance of high-risk sexual behaviors.

According to the School Health Profile report in 2016 that is undertaken every two years in the United States, only 29 % of schools in big cities had given education and necessary information to parents on how to communicate with children on sexual issues, which this figure was at a lower level in comparison with our results. But, 62 % of schools in the big cities in the United States had given the necessary information to parents for their child’s sexual issues monitoring, which in the current study, this figure was estimated at 36 %.

A study by Weaver et al. (20) demonstrated that although parents indicated that they wish to be involved in their child’s sexual health education, most of them had not discussed any sexual health education with their child. Parents also showed that they want more information from schools regarding sexual health education topics, sexuality in general, and communication strategies to assist them in providing education at home.

Using social organizations is one way to teach social skills and sex education for children and adolescents. Although these organizations can play a more active role in developing a trust-based relationship between parents and schools, the present study findings showed no collaboration between social organizations associated with health and family in more than half of schools. Hence, it seems necessary to adopt appropriate policies and programs to use these organizations’ potential in schools. In the United States, the partnership between families and social organizations has been estimated at 77.50 % (21), higher than our results.

Although increased family/community involvement in schools has been emphasized in the Fundamental Transformation Document of Education in the sixth national development plan of Iran (22), in this study, students’ families had active participation in developing and implementing policies and programs related to school health only in half of the schools. The parental involvement rate in developing and implementing policies and programs was at a moderate level, which affects the success rate of schools’ programs and policies, as active family engagement in schools’ planning and policymaking causes a sense of ownership and increased families commitment in the proper implementation of schools programs. The study of Kim et al. (13) has shown that family engagement can positively influence school nutrition and physical activity policies and practices.

The low family engagement in school health topics can arise from different reasons, such as many work and family businesses and time shortage. However, schools have not correctly understood the importance of family engagement in maintaining and promoting student health profile and have not carried out enough effort to attract their participation. The level of family involvement can be improved through attending children’s parents as representatives on schools’ boards or parent-teacher meetings. However, an essential issue in the development and implementation of family engagement strategies is to consider the socio-economic and cultural conditions of families, providing the possibility of family engagement. The study of Yolcu et al. (23) indicated that the effect of parents’ participation in school decision making varied in the socio-economic levels of the areas where schools were located, and also the difficulties experienced by the school administrators and parents in the process of their participation in schools varied with the socio-economic levels of schools.

Moreover, in designing health information content to increase families’ knowledge, most schools focused on healthy nutrition education, tobacco use prevention, physical activity, and diabetes, respectively. However, in designing educational content for parents, less than half of schools had addressed topics such as AIDS prevention, STD prevention, teen pregnancy, violence prevention, and cyber sexual harassment. In 2018, the prevalence of AIDS among people aged 15-49 years old in Iran was 0.1 %, and the number of people living with AIDS was 66,000, according to the statistics (9). AIDS prevention training is one of the topics that has been addressed in the field of socialization of health. Recently, easy access to electronic communication devices and the widespread attendance of children and adolescents in cyberspace have exposed them to a new type of violence called electronic aggression. Therefore, the prevalence of internet-harassment in adolescents has been reported as 1–61 % (24). This electronic aggression can have dangerous consequences on students and parents, leading to social isolation and suicide in adolescents later. Therefore, in educational content offered to families, some important issues such as social networks-related topics, communication applications, and monitoring of these networks’ use by children how to behave with cyber abuses should be included.

Given that necessary education for parents about tobacco use prevention is being performed in half of the schools. However, the prevalence of smoking, alcohol, chewing tobacco in Iranian adolescents aged 14-19 years old have been estimated at 17 %, 15 %, and 10 %, respectively (25). Since smoking usually occurs in early adolescence and continues until adulthood, proper and timely education for parents and adolescents can help prevent smoking’s adverse effects.

The finding of this study showed that only half of the schools had given homework or activities related to health education to students for being done at home with the participation of their parents, while in urban schools of the United States, this figure estimated at 62 % (26). Since doing homework at home is a tool for stabilizing learning in students, the quantity and quality of homework and parental participation in doing these should be in such a way that they boost the relationship between students and parents and improve students’ performance, and at the same time making a positive relationship between parents and teachers. The study of Núñez et al. (27) showed a reciprocal association between students’ achievement and parental involvement. They indicated that children’s achievements affect the rate and type of parental participation, and conversely, the student’s perception of their parent’s involvement in homework affects their achievements (27).

In the current study, lead health education staff worked with physical activity staff and the school health council in most schools. However, in some studies in Iran, the prevalence of depression among children and adolescents reported 43.55 % (28), and the majority of overweight and obese Iranian children aged less than five years were reported 9 % and 10 %, respectively (29). In comparison, overweight and obesity in children aged 7–18 were 9 % and 3 %, respectively (30). In this study, the participation rate of the staff of nutrition, social services, and mental health was lower compared to other related groups, which represents the failure to understand the importance of mental health topics for policymakers and authorities of health-promotion programs in schools.

Since the questionnaire was completed by the school principals and lead health education teachers, a self-report method was used to determine the level of family/community involvement in school health policies and programs, affecting the accurate estimation of participation level.

Conclusion

Given a low percentage of school and family/community partnerships in school

health-promotion programs in most dimensions, comprehensive and integrative planning is required to create engagement and collaboration with other community sectors.

Implications

The results of this study are indicative of the main frail of schools in attracting parental participation and their training regarding how to communicate with their child in the field of sexual topics and how to manage and monitor their children’s sexual behaviors, which increase the incidence of high-risk sexual behaviors among adolescents. Given that different social groups in terms of sexual literacy are at different levels, policymakers should perform educational policies based on educational groups’ needs and various areas. In other words, cultural and religious barriers in Iran have confronted transmission and education of sexual topics with the challenge. Besides, in many cases, sexual education topics will face the religious authorities’ opposition. Hence, the use of mass media to educate such topics considering Iran’s religious history required authorities’ support and commitment. Therefore, policies expanding in this domain should be formulated and implemented with the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Education, the Radio and Television Organization, non-governmental organizations, and the support of authorities. The present study also indicated that schools with groups such as nutrition or eating service staff, mental health or social services staff were at a lower level compared with other groups. So,

given the fundamental role of the two mentioned groups in students’ health promotion, enough concentration on attracting these groups’ participation by schools is necessary.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for supporting this research. We also wish to express thanks to individuals who participated in this study.

Conflict of interests

The authors declared no conflict of interests.

Authors’ contributions

Jalilian H and Khodayari-Zarnaq R designed research; Jalilian H, Heydari S, Torkzadeh L, Mir N and Rahmani H conducted research; Jalilian H and Heydari S analyzed data; and Jalilian H and Heydari S wrote manuscript. Jalilian H had primary responsibility for final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Tabriz

University of Medical Sciences (Grant Number: IR.TBZMED.REC. 64.61).

Type of Study: Original article |

Subject:

General

Received: 2021/01/29 | Accepted: 2021/10/4 | Published: 2021/10/4

Received: 2021/01/29 | Accepted: 2021/10/4 | Published: 2021/10/4

References

1. 1. Wechsler H. Why addressing health-related barriers to learning needs to be a fundamental component of school reform efforts. J Sch Health. 2011; 81(10): 1-3. [DOI:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00650.x]

2. (Inc.) W-WHPSA. Health promoting schools framework. Available from URL: http://wahpsaorgau/resources. Last access: 8 May, 2020.

3. IUfHP E. Achieving health promoting schools: Guidelines for promoting health in schools. Available from URL: https:// healtheducationresourcesunescoorg/ library/ documents/achieving-health-promoting-schools-guidelines-promoting-health-schools. Last access: 3 May, 2019.

4. Marzuki MA, Rahman S. Parental Involvement: A strategy that Influences a child's health related behaviour. Health Science Journal 2015; 10: 1-7.

5. Epstein JL. School, family, and community partnerships: Preparing educators and improving schools: Routledge. Available from URL: https://www.routledge.com/School-Family-and-Community-Partnerships-Preparing-Educators-and-Improving/Epstein/p/book/9780813344478. Last access: 3 April, 2019. [DOI:10.4324/9780429493133-1]

6. Prevention. CfDCa. Parent engagement: strategies for involving parents in school health. Available from URL: https://wwwcdcgov/ healthyyouth/protective/pdf/parent_engagement_strategiespdf. Last access: 8 May, 2020.

7. O'Dea J. Benefits of developing a whole-school approach to health promotion. Sydney University Press, Available from URL: https://ses.library. usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/12573. Last access: 20 July, 2020.

8. Division of population health NCfCDPaHP. Physical education and physical activity. Available from URL: https://wwwcdcgov/ healthyschools/physicalactivity/indexhtm. Last access: 8 May, 2020.

9. Kolbe LJ. School health as a strategy to improve both public health and education. Annual review of public health. 2019; 40: 443-63. [DOI:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043727]

10. Holmes BW, AllisonM, Ancona R, Attisha E, Beers N, Pinto C De, et al. Role of the school nurse in providing school health services. Pediatrics. 2016; 137(6). [DOI:10.1542/peds.2016-0852]

11. Nurses NAoS. Framework for 21st century school nursing practice: National Association of School Nurses. NASN School Nurse. 2016; 31(1): 45-53. [DOI:10.1177/1942602X15618644]

12. HEALTH COS. Role of the school physician. Pediatrics. 2013; 131(1): 178-82. [DOI:10.1542/peds.2012-2995]

13. Kehm R, Davey CS, Nanney MS. The role of family and community involvement in the development and implementation of school nutrition and physical activity policy. J Sch Health. 2015; 85(2): 90-9. [DOI:10.1111/josh.12231]

14. Afshani S, Janatifar A. The comparative study of social participation between state and non-profit high school students in Yazd and its relevant factors. Journal of Applied Sociology. 2016; 27(3): 73-96.

15. (CDC) CfDCaP. School health profiles. Available from URL: https://wwwcdcgov/ healthyyouth/data/profiles/indexhtm. Last access: 2 June, 2020.

16. Kehm R, Davey CS, Nanney MS. The role of family and community involvement in the development and implementation of school nutrition and physical activity policy. Journal of School Health. 2015; 85(2): 90-9. [DOI:10.1111/josh.12231]

17. Malek A, Shafiee-Kandjani AR, Safaiyan A, Abbasi-Shokoohi H. Sexual knowledge among high school students in Northwestern Iran. ISRN pediatrics. 2012; 2012: 645103. [DOI:10.5402/2012/645103]

18. Malek A, Bina M, Shafiee-Kandjani AR. A study on the sources of sexual knowledge acquisition among high school students in northwest Iran. Archives of Iranian Medicine. 2010; 13(6): 537.

19. Bahramitash R, Kazemipour S. Myths and realities of the impact of Islam on women: Changing marital status in Iran. Critique: Critical Middle Eastern Studies. 2006; 15(2): 111-28. [DOI:10.1080/10669920600762066]

20. Weaver AD, Byers ES, Sears HA, Cohen JN, Randall HE. Sexual health education at school and at home: Attitudes and experiences of New Brunswick parents. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality. 2001; 11(1): 19-32.

21. Brener ND, Demissie Z, McManus T, Shanklin SL, Queen B, Kann L. School health profiles 2016: Characteristics of health programs among secondary schools. Available from URL: https://stackscdcgov/view/cdc/49431. Last access: May 10, 2020.

22. The Islamic Republic of Iran Ministry of Education SCoCR, Supreme Council of Education. Fundamental Reform Document of Education(FRDE) intheIslamic Republic of Iran. Available from URL: http://enoerpir/sites/ enoerpir/files/sandtahavolpdf. Last access: 12 May, 2020.

23. Yolcu H. Decentralization of education and strengthening the participation of parents in school administration in Turkey: What Has Changed? Educational Sciences. Theory and Practice. 2011; 11(3): 1243-51.

24. Brochado S, Soares S, Fraga S. A scoping review on studies of cyberbullying prevalence among adolescents. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2017; 18(5): 523-31. [DOI:10.1177/1524838016641668]

25. Ghodsi A, Balali E, Latifipak N. A study of effects of social factors on parents, participation in Hamadan senior high schools. Quarterly Journal of Social Development (Previously Human Development). 2017; 12(1): 81-106.

26. Brener ND, Demissie Z, McManus T, Shanklin SL, Queen B, Kann L. School health profiles 2016: Characteristics of health programs among secondary schools. Available from URL: https://wwwcdcgov/healthyyouth/data/profiles/pdf/2016/2016_Profiles_Reportpdf. Last access: 8 May, 2020.

27. Núñez JC, Epstein JL, Suárez N, Rosário P, Vallejo G, Valle A. How do student prior achievement and homework behaviors relate to perceived parental involvement in homework?. Frontiers in Psychology. 2017; 8: 1217. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01217]

28. Sajjadi H, Kamal SHM, Rafiey H, Vameghi M, Forouzan AS, Rezaei M. A systematic review of the prevalence and risk factors of depression among Iranian adolescents. Global Journal of Health Science. 2013; 5(3): 16. [DOI:10.5539/gjhs.v5n3p16]

29. Mansori K, Khateri S, Moradi Y, Khazaei Z, Mirzaei H, Hanis SM, et al. Prevalence of obesity and overweight in Iranian children aged less than 5 years: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Korean Journal of Pediatrics. 2019; 62(6): 206-12. [DOI:10.3345/kjp.2018.07255]

30. Mirmohammadi S-J, Hafezi R, Mehrparvar AH, Rezaeian B, Akbari H. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among Iranian school children in different ethnicities. Iranian Journal of Pediatrics. 2011; 21(4): 514.

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |